Learn More

Learn more about the Santa Cruz River, its environment and wildlife, and its use in our community.

Learn about: The River | Riparian Ecosystems | Sewage Pipe Threat

Introduction

About the Santa Cruz River

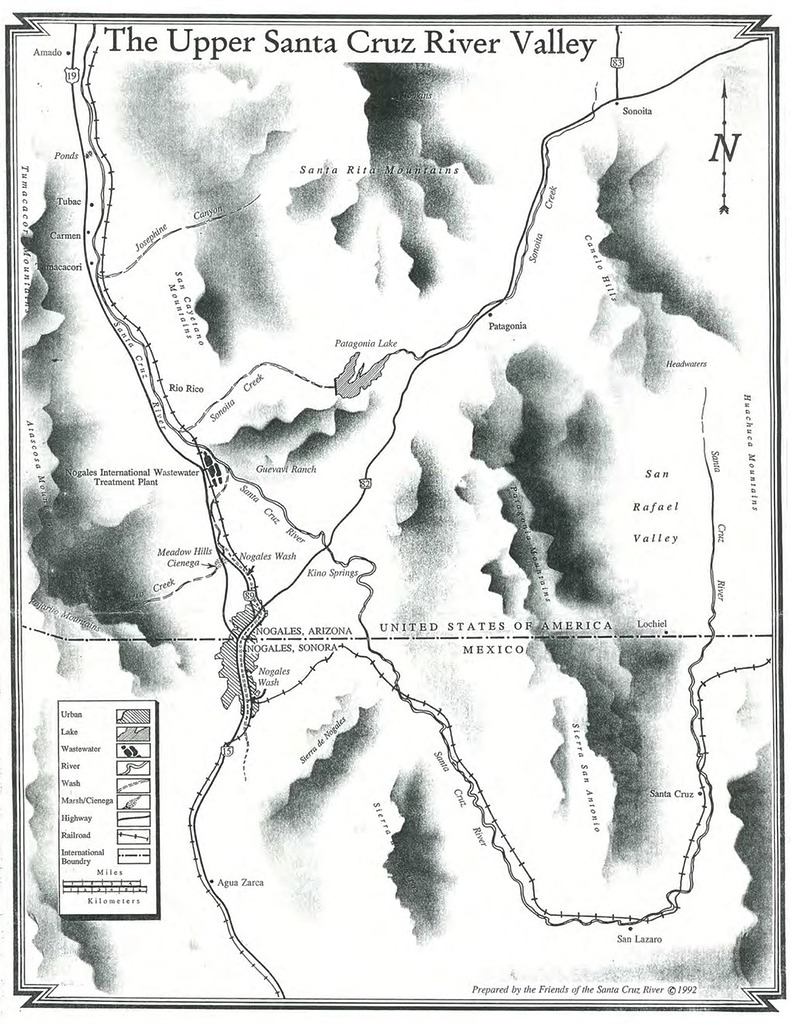

An actual, wet river flows through the heart of Santa Cruz County, on the border of Mexico in southern Arizona. Considering the fate of most river systems in the southwest, the Santa Cruz River is a bit of a miracle. Humans first caused the downfall of the living river, and then were responsible for its resurrection. It once again brings life and special meaning to our valley. And again, we hold its future, and all the benefits it provides to us, in our own hands.

The river slides through dense stands of cottonwood and willow. Flanking these gallery forests, the remnants of mesquite-dominated riparian “bosques” (Spanish for woodlands) cover the soft, deep soil with elderberry, hackberry, ash and walnut. Native fish swim in the river’s gentle current. Fox, deer, raccoons and the occasional cougar drink its cool water and find or catch their food here. A multitude of birds gorge on the food its plants produce and nest in the sheltering foliage. Although it’s only inches deep in most seasons, the Santa Cruz’s influence is outsized. Its green lushness stands in stark contrast to the adjacent hills that struggle to host sparse desert grasses, prickly shrubs and stunted trees on their thin rocky soils.

Download a free PDF map:

A Rambler’s Guide

The Life of the Santa Cruz River

Explore A Rambler’s Guide, a beautifully illustrated look at the plants, wildlife, and history of the Santa Cruz River. This guide highlights the rare ecosystems that survive along the river’s flow and gives tips for discovering “a wealth of living surprises.”

Riparian Ecosystems

What Is A Riparian Ecosystem?

Riparian ecosystems are made up of the plants and animals living along lakes, rivers, and streams, and the soil, air and water that support them.

They include areas within floodplains that may only rarely see surface flows, but where the “water table” (top of the aquifer, below which the ground is saturated) is shallow enough for plant roots to reach subsurface water.

Here in the arid Southwest, riparian ecosystems are easy to spot, because while shallow groundwater underlies river bottoms, plants on the surrounding uplands—higher terrain with water only far beneath the surface—have to live on scarce rainfall. So the plant types and densities near the river (“riparian”) can be quite different than those living above floodplain levels. Shallow-rooted cottonwoods and willows can thrive less than fifty feet from desert grasslands that cover the higher slopes surrounding them.

To learn more, download the Arizona Riparian Council’s Fact Sheet.

Why Are Riparian Ecosystems Important?

Riparian areas provide many benefits to both people and wildlife:

They enhance groundwater recharge (groundwater is where everyone in southern AZ gets our water) by maintaining a layer of spongy soil that can quickly absorb and hold rainfall, as well as developing complex root systems that help water infiltrate into the ground.

- They provide many opportunities for hiking, horseback riding, birding and other recreational activities.

- They improve water quality by filtering runoff through sediments, roots, and living soils.

- They provide critical habitat for many wildlife species, some of which live only in riparian areas.

- They prevent widespread erosion by stabilizing soil and absorbing the force of large flood events.

Is Riparian Conservation Needed?

Riparian ecosystems are in trouble in many parts of Arizona. Along the Santa Cruz River the combined effects of drought, groundwater pumping, flood control measures, water diversions and other human activities have damaged or destroyed many of the cottonwood and willow trees that used to thrive along portions of this river. The picture to the left shows the extensive tree die-off that occurred in the Spring of 2005, most likely from a rapid drop in the water table below the tree roots.

Also, the once-extensive mesquite/elderberry/hackberry forests that flanked the Santa Cruz all the way to Tucson have been largely cleared for agriculture and other human uses.

However, there is still a lot of riparian life to save along the upper Santa Cruz River and its tributaries. This is FOSCR’s mission: to protect, celebrate, and if possible enhance the biological bounty that the river supports.

Learn more about the loss of U.S. wetlands at the U.S. Geological Survey website.

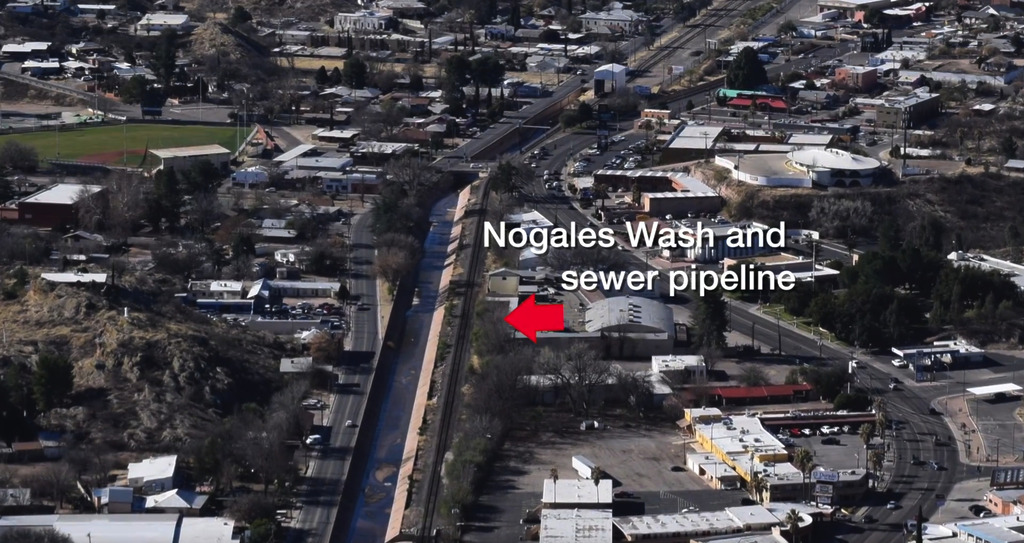

International Outfall Interceptor

Eroding Sewer Pipe Threatens Santa Cruz River

“The Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant provides secondary treatment for wastewater generated in both Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora. Owned by the United States Section of the International Boundary and Water Commission (USIBWC) and the City of Nogales, Arizona, the plant is operated by the USIBWC. Operating costs are shared by the USIBWC, Mexico, and the City of Nogales, Arizona, making the treatment plant a truly binational endeavor. The plant has a capacity to treat up to 17.2 million gallons per day of sewage. The wastewater goes through several treatment steps before the disinfected effluent is discharged into the Santa Cruz River. The plant’s treated effluent is considered a resource to the community, providing valuable riparian habitat in the river corridor.”

– International Boundary and Water Commission, 2023

Watch the April 2025 Southeast Arizona Citizen’s Forum Meeting.

Development/ Land Use

Balancing Growth and Conservation in the Santa Cruz River Watershed

Not only does a river need water of an adequate quality to support a significant riparian ecosystem– it also needs a healthy watershed. The watershed is the entire area that drains into the river; its edges run along the peaks of all the surrounding highlands and mountains. The quality of the land that rain runs across on its way to the river makes a big difference to both the resulting water quality in the river and its flow characteristics.

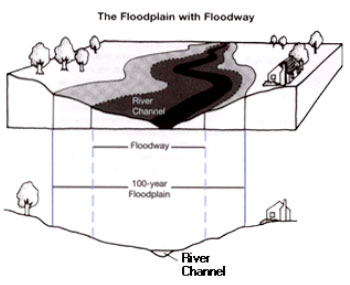

Within the watershed, all rivers specifically need a functioning floodplain if they are to bring all their potential benefits to the communities they flow through. The floodplain is the part of the watershed that is periodically flooded near the river; it is generally flatter than the surrounding terrain. A broad, tree-filled floodplain built up with rich, spongy soils will absorb, slow and spread torrential floodwaters much more effectively than will a narrow, barren floodplain. Imagine a cement-lined canal as the ultimate non-functioning floodplain, and you can appreciate the difference.

FOSCR works with landowners and local and State agencies to protect the river by protecting, or improving, watershed lands and our functional floodplain through:

- Monitoring County regulation of building/development practices to assure that the long-term health of the watershed is maintained in the face of development;

- Encouraging the techniques of water harvesting to keep water close to where it falls, so it can percolate into the ground;

- Supporting “best management practices” on grazing lands

Resource Library | Watershed Management Group and Stormwater & Watershed Management